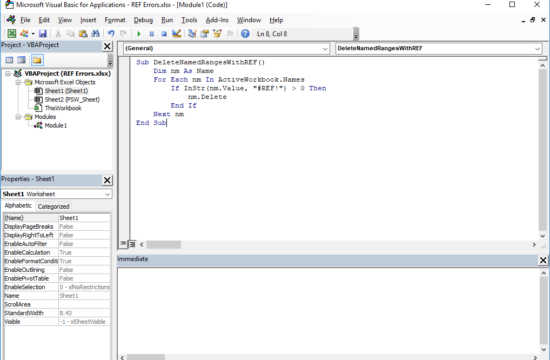

WHAT’S DIRECT-TO-CONSUMER (DTC)?

Direct-to-consumer (or DTC or D2C) has created quite a shift in the dynamics of the retail industry.

Why? Because it allows businesses to cut out the retailer and distributor intermediary, thereby going direct to the consumer.

In a DTC retail model, businesses manufacture and ship their products direct to consumers – not via traditional stores or other middlemen. In-so-doing, they can sell their products at lower cost and maintain end-to-end control over their products – and the customer.

Brands in categories such as apparel and electronics have successfully established a new distribution channel by selling direct-to-consumer (DTC). A good example of this is Nike – its products can be found in both generalist and specialist retailers, as well as being available through its own stores and eCommerce site. Electronics brands such as Samsung and Sony have also recognised the many benefits of selling DTC, such as end-to-end management of the consumer experience and ownership of consumer data.

However, CPG/FMCG brands have been slower to move into the direct-to-consumer space for reasons such as:

■ Fear of channel conflict (where DTC is perceived as a threat by existing distributors)

■ Lack of compelling consumer value proposition (what is the reason a shopper should buy direct from the brand

rather than their usual source)

■ Complexity of developing new capabilities (traditionally brands have isolated pockets of digital skills and

knowledge and processes are optimised for B2B business models)

■ High operational set-up costs (high upfront investment to set up the infrastructure needed for a direct

selling business)

Despite these challenges, the large conglomerates like Unilever and P&G have been forced to consider DTC as a potential sales channel because of the threat imposed by niche DTC start-up brands who have quickly amassed a consumer base through their online stores. These digitally native brands don’t have the legacy business models or scale of operations to accommodate, and so can be more nimble and single-minded in their approach.

There are a multitude of ways to handle the challenges mentioned above; here are 4 ways the dominant international multi-brand corporations have approached the threat and opportunity of DTC:

- Create a new brand

This solution addresses the potential of channel conflict – there is no conflict if the sole distribution path is through the brand’s own online store, thus avoiding the awkward conversation with retailers about the brand owner launching a competing route to market through DTC.

Example: L’Oréal “Color&Co”

In the US, L’Oréal has just launched a new hair colouring brand Color&Co which is only available DTC. The site allows consumers to have a video consultation with an independent colourist who will make a unique custom-made product which is delivered to the shopper’s home. - Value proposition

Consumers need a compelling reason to change their shopping behaviours. Brands need to provide a reason for the customer to shop on brand.com – that’s a brand’s website – rather than their regular source. A popular solution to this challenge is to provide personalised or exclusive products on brand.com, or to offer

subscription services which are convenient for shoppers but advantageous to the brand because the shopper is “locked in”.

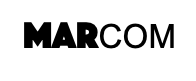

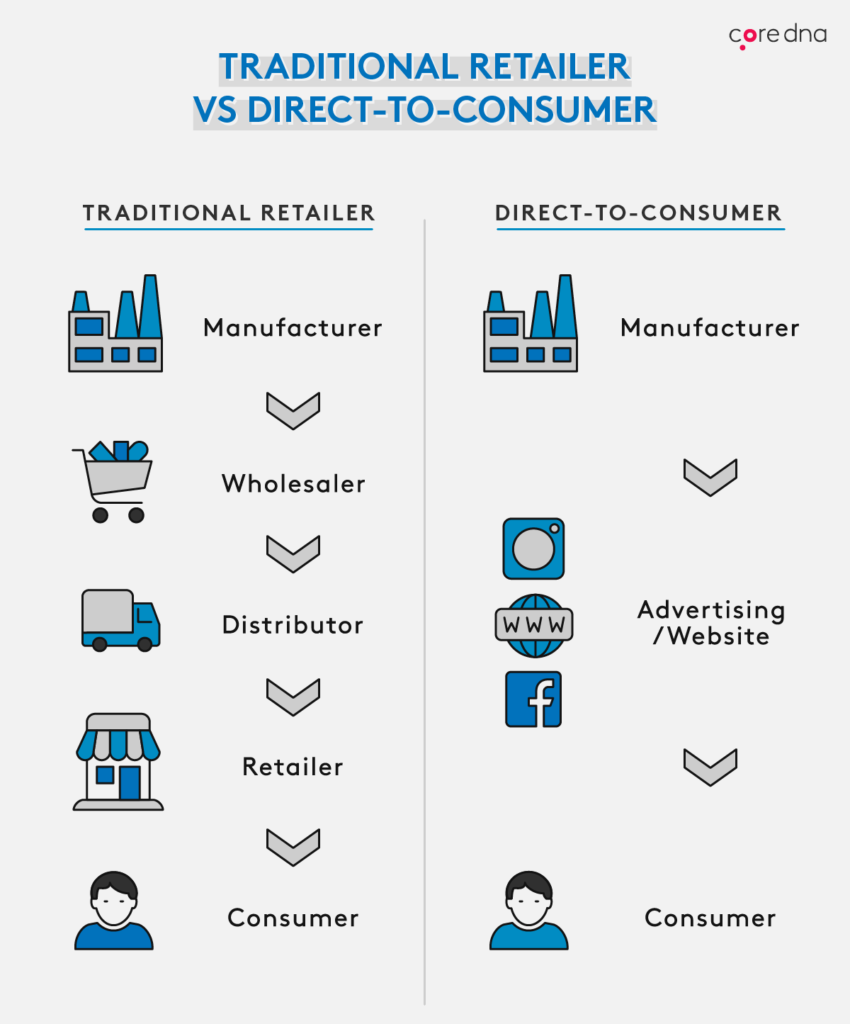

Example: Mars “M&M’s”

Capitalising on the gifting market, M&M’s DTC site allows shoppers to personalise products by choosing colours and adding images and text. - Acquisition

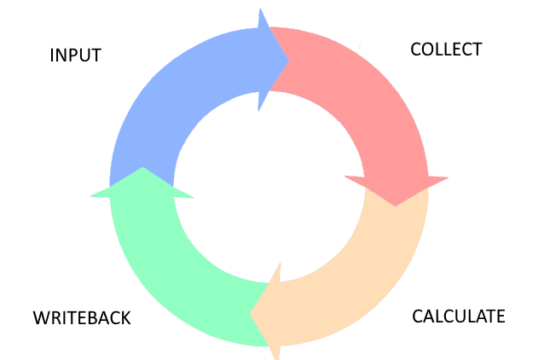

Large traditional organisations face the laborious and costly task of expanding their competencies to enable them to sell online direct-to-consumers. For example, they will need to develop new capabilities around logistics (to fulfil single unit orders to consumers’ homes), technology (for a transactional website) and customer services

(to manage customer order queries and returns processing). Acquiring digitally native, niche DTC brands addresses this problem and enables the large brands to implant the skills and expertise of the acquired business into the existing brands.

Example: Kellogg’s “Bear Naked”

Bear Naked granola was started in 2002 by a couple of American high school friends. Such was the brand’s success, it soon attracted the attention of Kellogg’s who purchased the business in 2007.

In 2016, the brand launched Bear Naked Custom, a website allowing consumers to create their own customised granola by combining over 50 ingredients. The innovative proposition uses IBM’s technology (Chef Watson) to support consumers’ discovery of unexpected combinations,

using unusual ingredients such as Bourbon, jalapeños and lavender.

The website also allows the packaging to be customised with photos and personalised messaging in the form of a “story” printed on the canister. - Partner

An alternative to acquiring eCommerce capabilities through buying a DTC competitor is to partner with a digital specialist. In the UK, The Hut Group is complimenting its pure-play retail business with a “white-label” proposition in which it supplies website, fulfilment and back-end operational capabilities to brands wanting to launch DTC.

The Gillette subscription site mentioned previously is an example of a DTC site operated by The Hut Group.

CONCLUSION

The multi-brand CPG giants are seizing the direct to consumer opportunity through different approaches. Key components for these types of initiatives include board level support and investment as well as an entrepreneurial mind-set. Although a direct-to-consumer channel approach may not be a short term sales driver, there is clearly strategic value in incorporating DTC into a brand’s eCommerce strategy.